News

Fewer homeless people sleeping on S’pore streets last year; city area has highest number

The number of homeless people in Singapore fell slightly last year, at a time when homelessness was on the rise in many countries amid the Covid-19 pandemic.

But the issue of homelessness also became less visible, as more people who would have slept on the streets went to stay at temporary shelters.

The competition was organised by City Harvest Community Services Association and received support from FUN! Fund, a Community Impact Fund jointly established by the Community Foundation of Singapore and the Agency for Integrated Care, with the aim of addressing social isolation among the elderly.

The second nationwide street count of the homeless here found 1,036 people last year – 7 per cent less than the 1,115 people during the first such count in 2019.

That first nationwide street count has been described as a landmark study of an issue that was hidden from public discourse until recent years.

While the overall number has fallen slightly, where the homeless make their bed for the night has also changed.

The second street count found that those sleeping on the streets fell by 41 per cent from 1,050 in 2019 to 616 last year, while those staying at a temporary shelter for the homeless shot up from 65 to 420 in the same time period.

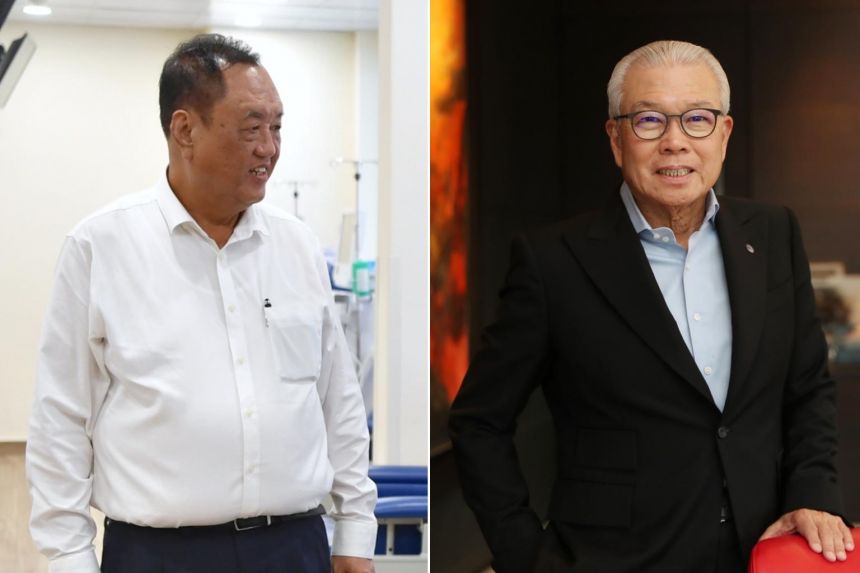

Dr Ng Kok Hoe, a senior research fellow at the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy, led a team of researchers at the school’s Social Inclusion Project to do the street count. They were aided by over 200 volunteers who pounded the streets, including combing 12,000 blocks of flats, late at night between February and April last year to count the number of people sleeping in public spaces.

The data on the number staying at temporary shelters for the homeless, which was provided by the Ministry of Social and Family Development (MSF), was included for the first time in last year’s count for a fuller understanding of the state of homelessness here.

The 78-page report was released on Thursday (Aug 11). The project was not commissioned by the Government and was funded by the Community Foundation of Singapore, Dr Ng said.

He said government agencies and volunteers reached out to those sleeping rough during the circuit breaker in 2020 to refer them to shelters and many of the homeless, who were also concerned about their health and safety, decided to go into one.

Some religious and charity groups opened their premises for the homeless for the night, as demand for places in such Safe Sound Sleeping Places soared. Two new transitional shelters, which offer a longer stay, also started operation in January last year, the report said.

These factors led to more staying at shelters and fewer on the streets, Dr Ng said.

From the second street count, the homeless were found sleeping in most parts of Singapore, from Bedok to Jurong West to Yishun. But more of them were found in larger, older and poorer neighbourhoods.

Some 72 persons were found sleeping in the City area, or downtown, which has the largest number of homeless persons.

The city area, or downtown, has the largest number of homeless people, though it fell last year from the 2019 count.

Most of the homeless are elderly men and the report pointed out that few women sleep on the streets due to safety concerns.

Last year’s count found a sharp decline in those sleeping rough in commercial buildings, like shopping malls and office blocks, and more slept at places like void decks, parks and playgrounds.

The report pointed out that while the pandemic triggered their admission into a shelter, the homeless person’s housing woes started long before Covid-19 struck.

Highly subsidised public rental housing will always be the last safety net for the most vulnerable, Dr Ng said.

However, he singled out the design of the Joint Singles Scheme, which is under the public rental housing scheme, as a “significant contributing factor to homelessness”. This is because two singles, who are often strangers, share a tiny HDB rental flat which usually have no bedrooms, and the lack of privacy or personal space may lead to conflict.

And some would rather sleep on the streets instead, he said.

The HDB and the Ministry of National Development (MND) recognise the challenges some have applying for or sharing a rental flat and they have been reviewing and adjusting the Joint Singles Scheme in recent years, the MSF said in a statement in response to the street count.

For example, since December last year (2021), the HDB and MND started a pilot scheme where social service agencies match tenants with similar preferences and habits to share a flat. Under this pilot, singles can apply for a public rental flat by themselves, without having to find a flatmate first.

Flats under this pilot come with partitions installed

Applicants’ eligibility and rent are assessed individually.

The HDB and MND are assessing the effectiveness of this pilot project to see whether to scale it up over time, the statement said.

The MSF said there has been a steady and collective progress in whole-of-society efforts to reach out to and support rough sleepers, to help them off the streets and into shelters.

It cited the 57-member Partners Engaging and Empowering Rough Sleepers (Peers) Network, which comprises government agencies, religious groups and charities working together to ensure better coordination and synergy in the delivery of services to help the homeless.

The network’s partners have set up Safe Sound Sleeping Places. There are now about 20 such Places, which shelter about 100 homeless individuals. In addition, there are currently six transitional shelters serving families and about 270 individuals.

Since April 2020, over 680 homeless individuals who stayed at the various shelters have moved on to longer-term housing.

And since April this year, the MSF has been working with partners from the Peers Network and academic advisers to plan regular street counts. The first such coordinated street count will take place by the end of the year.

It said: “The street count will help us to collectively better understand the scale and geographical spread of rough sleeping in Singapore and render coordinated support to rough sleepers in need.”

Who were the homeless during the pandemic

| Long-term homeless (those who were homeless before the pandemic) | Newly homeless (those who had not slept rough before the pandemic) | Transnational homeless (Singaporeans who live in Indonesia and Malaysia but travel to Singapore for work) | |

| Sex | • More men than women | • Mix of men and women | • Almost all men |

| Age | • From 30s to 70s | • From 30s to 70s | • Mostly in their 50s |

| Family relationships | • Almost all divorced, separated or never married • Having past conflict and estrangement, with many having lost contact with their family | • Almost all divorced, separated or never married • Family relationships distant and strained, but connection remains | • Long-term drift and overseas travel • Some had a spouse and young children in their adoptive countries whom they are still connected to |

| Work and finances | • Low-wage and insecure jobs • Extreme poverty | • Low-wage and insecure jobs, with a few having had better paying jobs in the past • Difficulty meeting basic needs | • Regular border crossings for low-wage and insecure jobs in Singapore • A few did informal work outside Singapore • Low income |

| Housing histories | • Lost matrimonial home or never purchased housing • Encountered barriers in public rental system • Episodes of low- cost market rentals | • Lost matrimonial home or never purchased housing • Moved frequently to stay with family, friends • In low-cost market rental units | • Lived in Malaysia or Indonesia • Encountered difficulties obtaining public housing in Singapore for non-citizen family members |

| Rough sleeping | • From a few months to many years | • No more than a few days when displaced during the pandemic | • A mix of experiences, from rough sleeping to staying in homeless shelters |

| How they entered a shelter* | • Found by volunteers or field workers while rough sleeping during pandemic • Some self-referrals | • Self-referrals when pandemic disrupted housing arrangements | • Most were stopped at immigration checkpoints and directed to a shelter after border closures** |

*Homelessness counts usually include both rough sleepers (primary homelessness) and persons in homeless shelters (secondary homelessness).

**Those entering Singapore from Malaysia just before the borders were closed were identified as having no housing and referred for assistance so they could comply with Covid-19 rules on staying indoors

Table: STRAITS TIMES GRAPHICS Source: LEE KUAN YEW SCHOOL OF PUBLIC POLICY

If you would like to know more about the Sayang Sayang Fund, please visit here. This article was originally published in The Straits Times here. Source: The Straits Times © SPH Media Limited. Permission required for reproduction.

- Related Topics For You: COMMUNITY IMPACT FUND, DIRECT AID, DONOR STORIES, INCLUSIVITY & INTEGRATION, NEWS, PARTNERSHIP STORIES, SAYANG SAYANG FUND

Trending Stories

Karim Family Foundation: Donor-Advised Fund Raises $200,000 to Support Local Sports Champion Loh Kean Yew

Karim Family Foundation: Donor-Advised Fund Raises $200,000 to Support Local Sports Champion Loh Kean Yew

In December 2021, 24-year-old Loh Kean Yew became the first Singaporean to win the Badminton...

‘I thought I couldn’t go through any more of it’: Cancer patient gets help after insurer says ‘no’ to $33k bill

‘I thought I couldn’t go through any more of it’: Cancer patient gets help after insurer says ‘no’ to $33k bill

Good Samaritans have stepped forward to help a cancer patient, who hopes to spend more...